| tags: [ cycling ]

Changing Gears

Everyone who’s been on a bike knows the trade-off: fast and easy pedaling (low gear) or slow but strenuous pedaling (high gear). I shifted gears while students felt the difference, pedaling with their hands. Marking the rear wheel with a piece of tape, we counted how many times it spun for each turn of the pedals. In gears where pedaling was difficult, the rear wheel turned more.

Gears and shifters make bikes heavier, more expensive, and more vulnerable to malfunction, but they let us trade forward motion for ease of pedaling.

Now let’s make this observation precise: Exactly how far forward does the bike travel for a given amount of pedaling? (Sheldon Brown named this handy measure the “gain ratio.”)

$$ \text{Gain Ratio} = \displaystyle\frac{\text{Wheel Size}}{\text{Pedal Crank Size}}\times\frac{\text{Teeth on Front Gear}}{\text{Teeth on Rear Gear}} $$

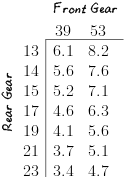

The first fraction is fixed on a given bike; only the second fraction changes with shifting. On my Bianchi, the first fraction is 340 mm / 170 mm = 2. By counting the teeth on the front and rear gears, we can compute the gain ratio for all 14 “speeds” (gear choices).

To interpret this table of gain ratios, take for example the highest one, 8.2. It comes from choosing the large gear in front (53 teeth) and the smallest gear in back (13 teeth). For each mile that my foot travels through the pedal’s circular path, the bike moves 8.2 miles forward.

If I shifted into the small gear in front and the largest gear in back, my bike would only travel 3.4 miles for every mile of pedaling. Pedaling would be correspondingly easier.Other observations:- There’s a fair amount of redundancy. In this table of 14 “speeds,” there are only about 10 distinct gain ratios.

- The dynamic range is about 2. That is, the hardest gear is twice as difficult as the easiest gear.

- “Easiness of pedaling” is measured by mechanical advantage, which is the inverse of the gain ratio.

$$\text{Mechanical Advantage} = \displaystyle\frac{1}{\text{Gain Ratio}}$$